CLICK HERE to continue reading full text on this page or download below

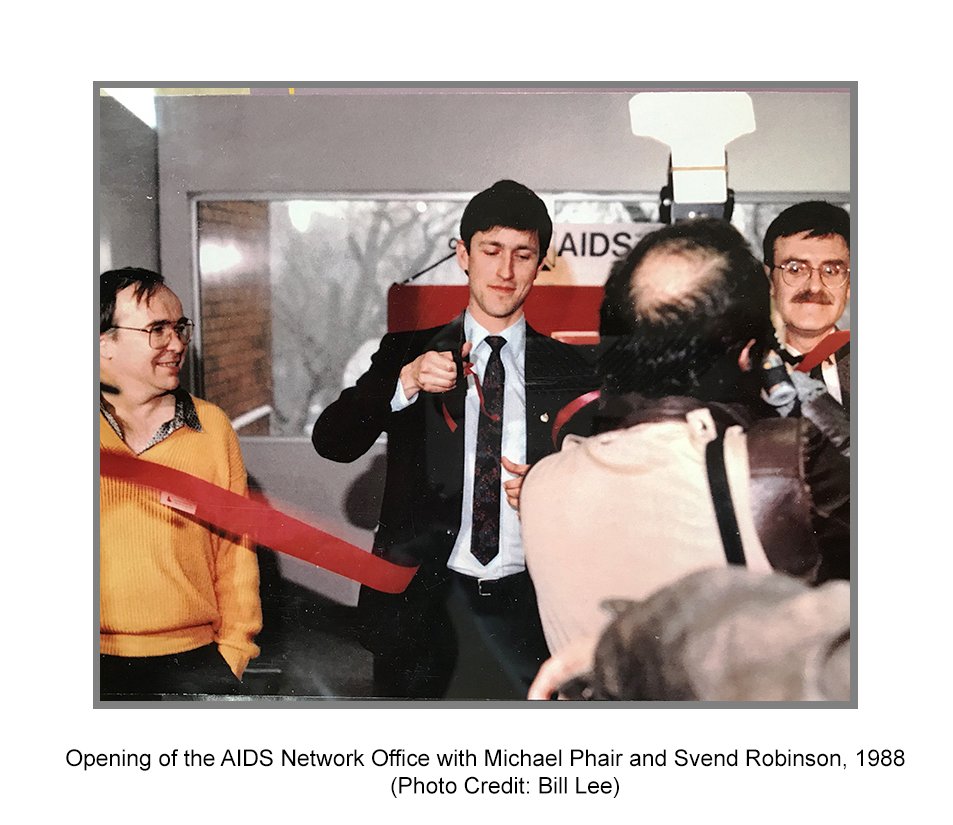

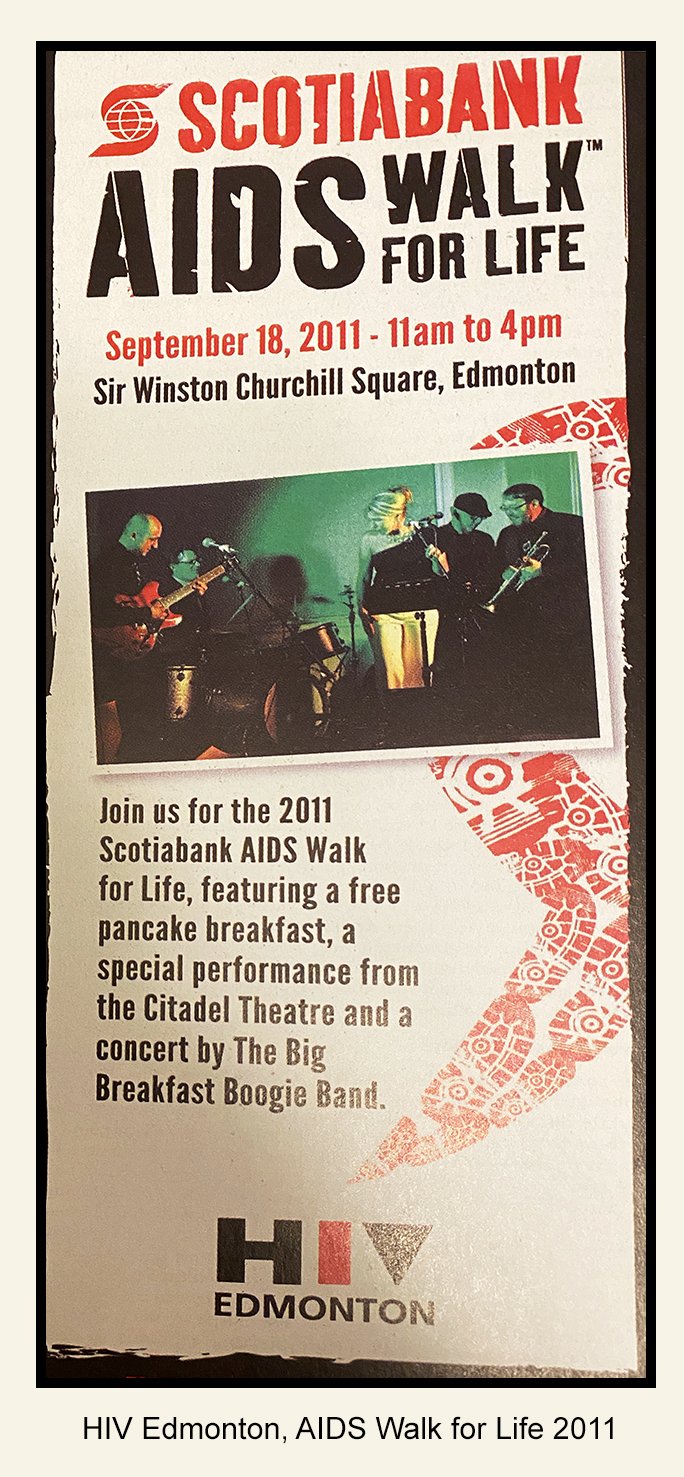

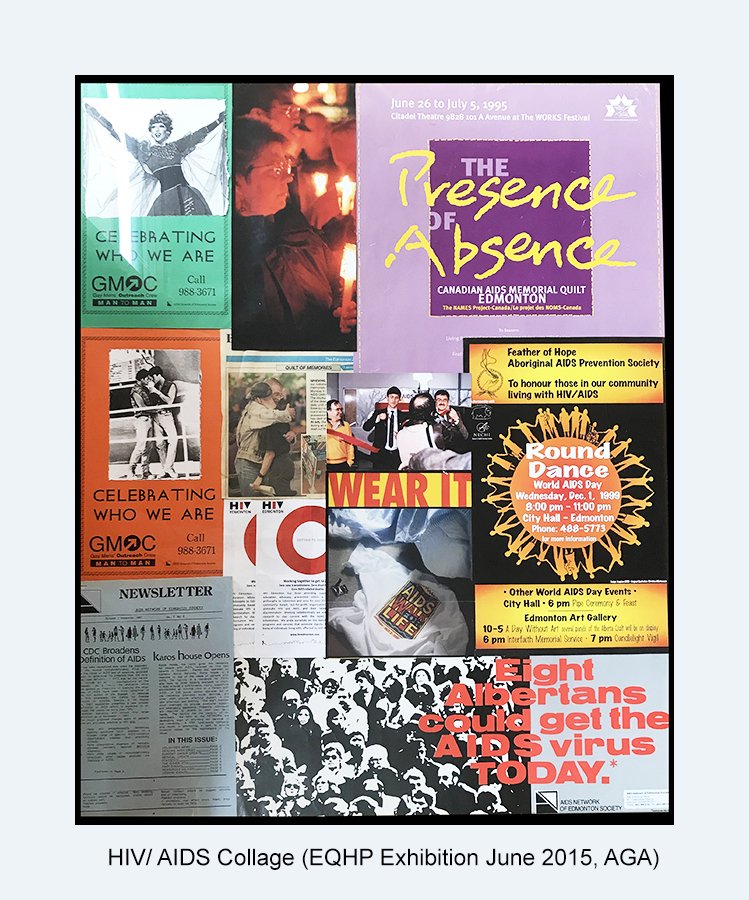

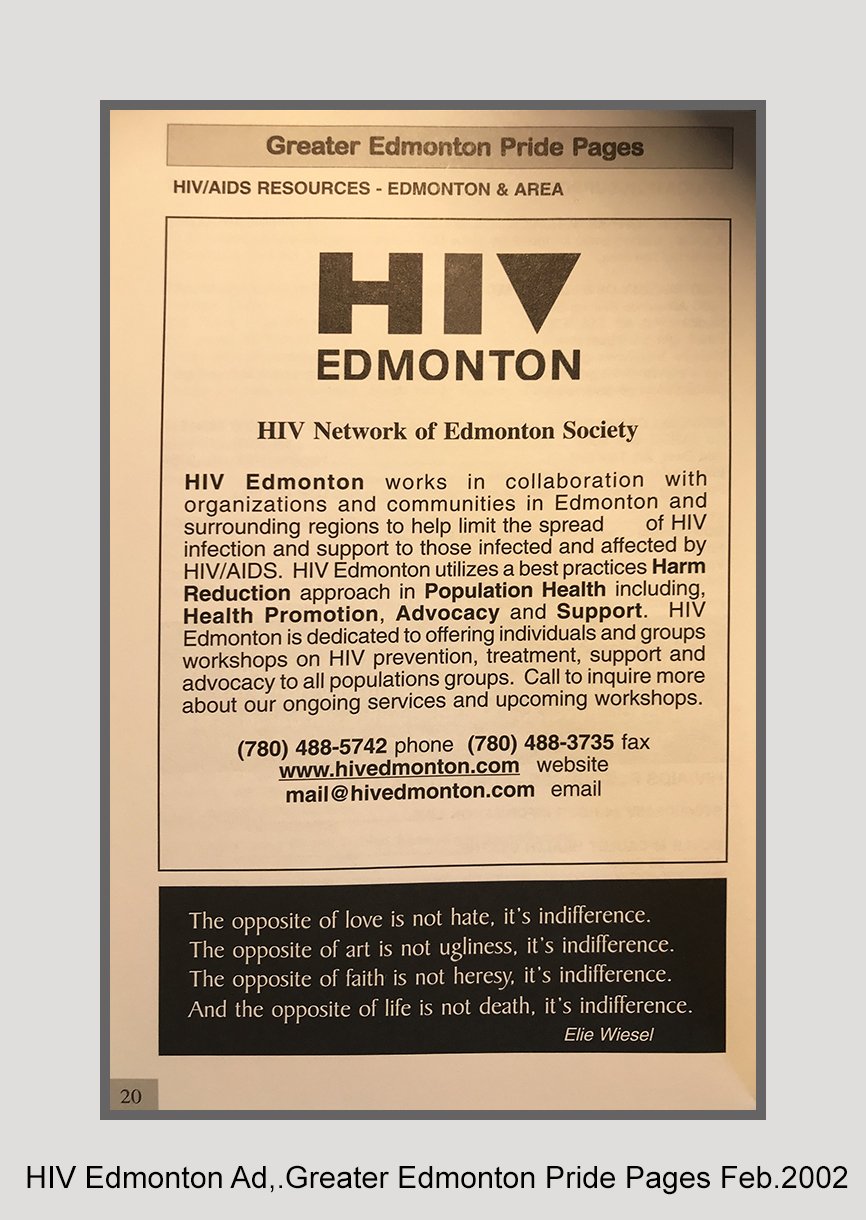

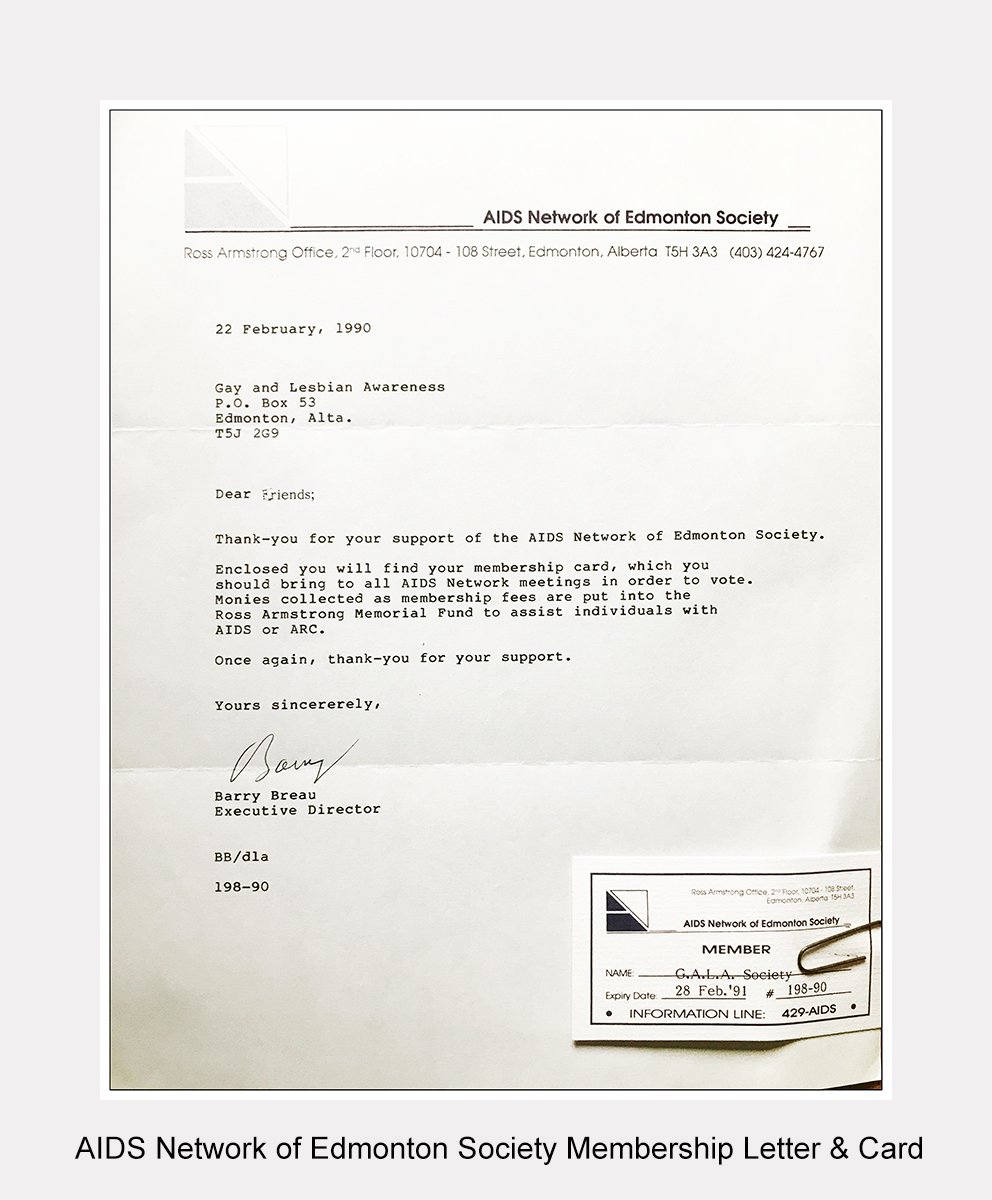

The historian Valerie Korinek argues that in the mid-1980s, when AIDS arrived in Edmonton, “there was an explosion of organizational development, activism, and attention paid to gay men (in particular), which stimulated health activism.” In fact, by 1985, “AIDS had arrived in all the prairie cities” and “dramatically transformed the organizational, activist, and queer communities” as “attention turned from liberationist goals to medical advocacy and support.” Several organizations emerged in Edmonton, including the AIDS Network of Edmonton, which was established in 1984 and later renamed HIV Edmonton in 1999. In 1987, Kairos House was established by Catholic Social Services to provide accommodations and supports for individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Both HIV Edmonton and Kairos House still operate and provide essential services to this day.