CLICK HERE to continue reading full text on this page or download below

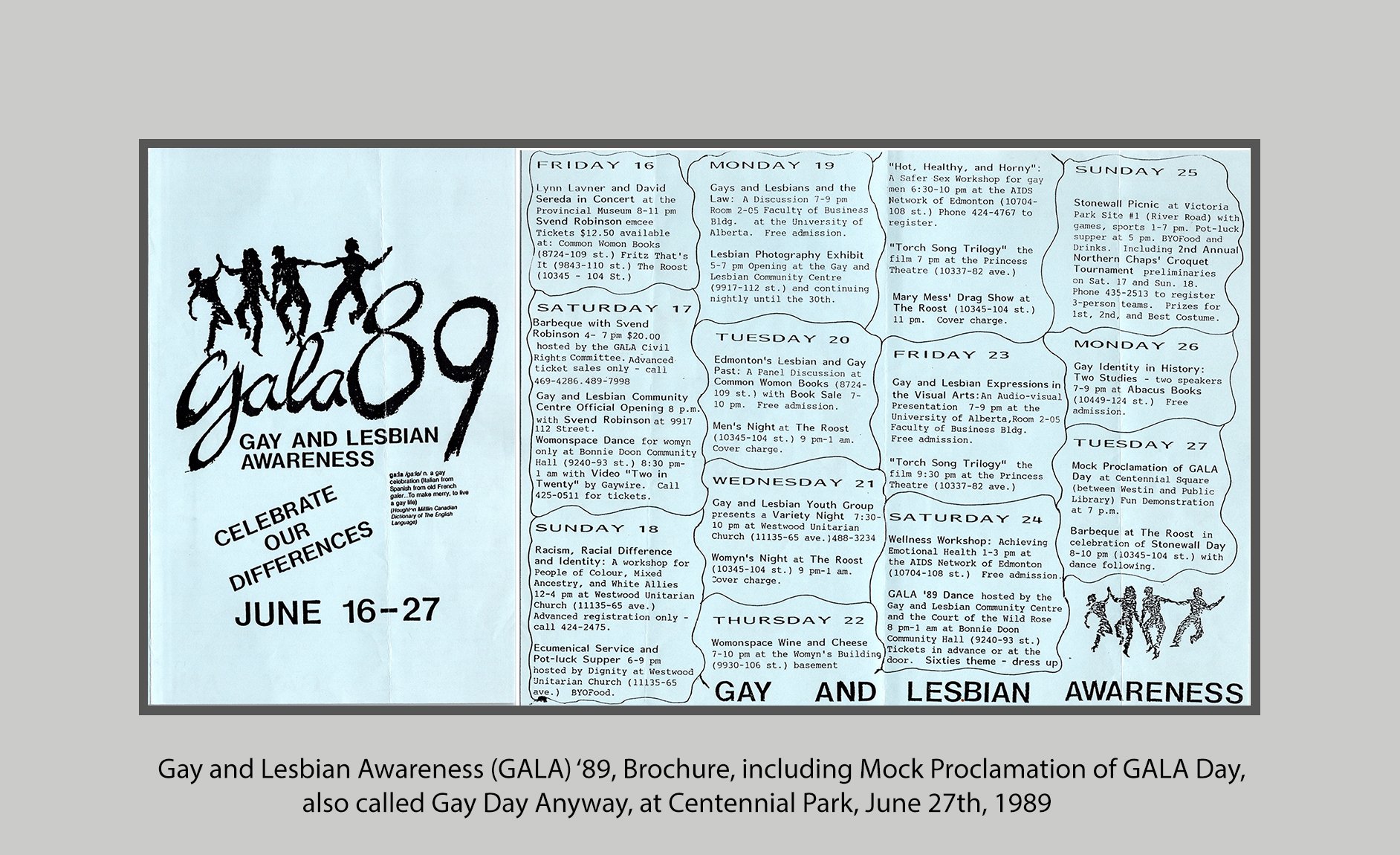

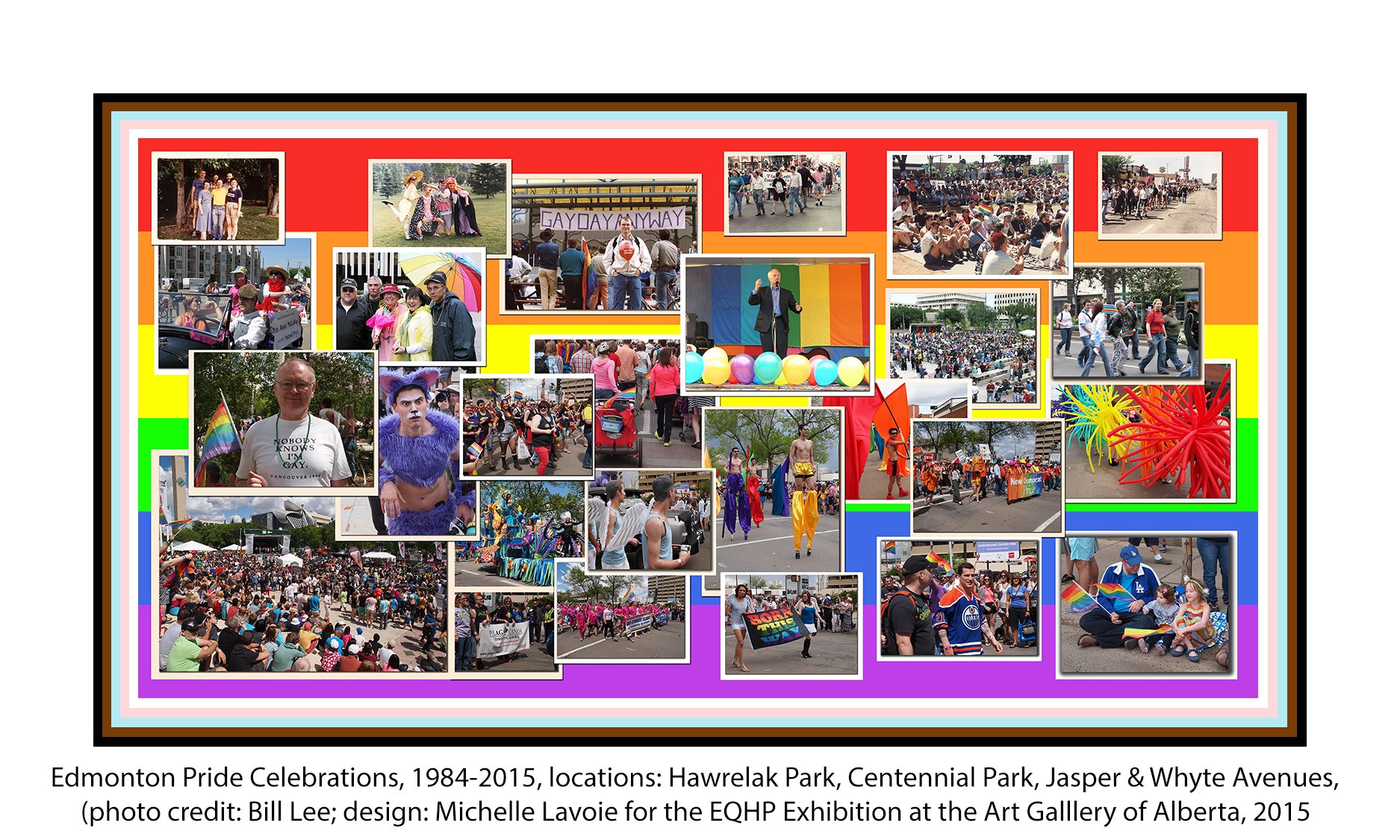

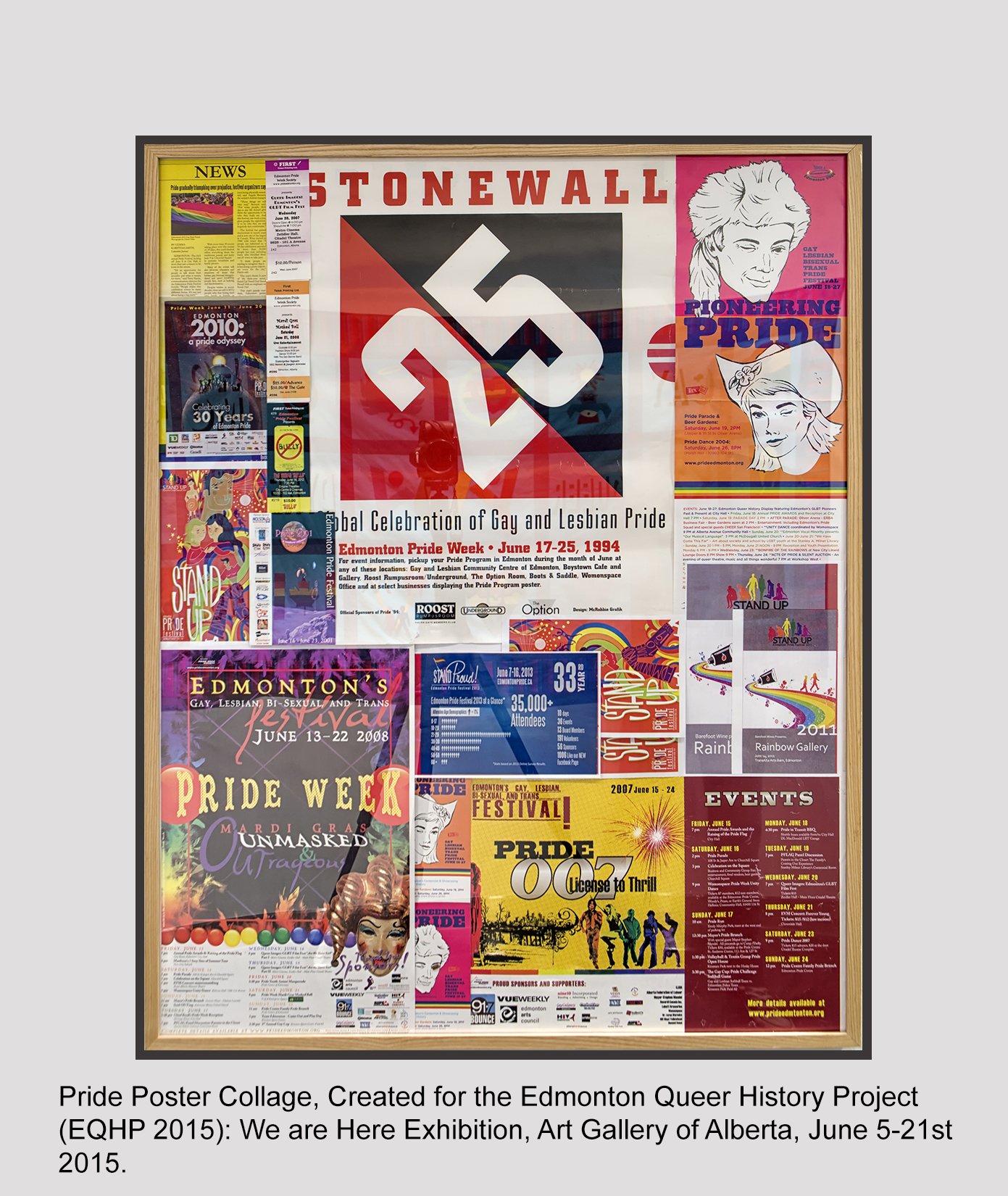

The year 1989 was, of course, not the first year Pride events were held in Edmonton. Even before the 1981 police raid of the Pisces Health Spa, local LGBTQ2 venues and groups such as GATE and Dignity had celebrated Pride with various activities, which were often held at Camp Harris, located just west of the city. These events usually occurred quietly inside the local LGBTQ2 community, without much fanfare or mainstream media attention. After the 1981 raid, a media spotlight began to grow and follow gay and lesbian community advocates who were fighting back against oppression and advocating for equal rights in all aspects of society.