CLICK HERE to continue reading full text on this page or download below

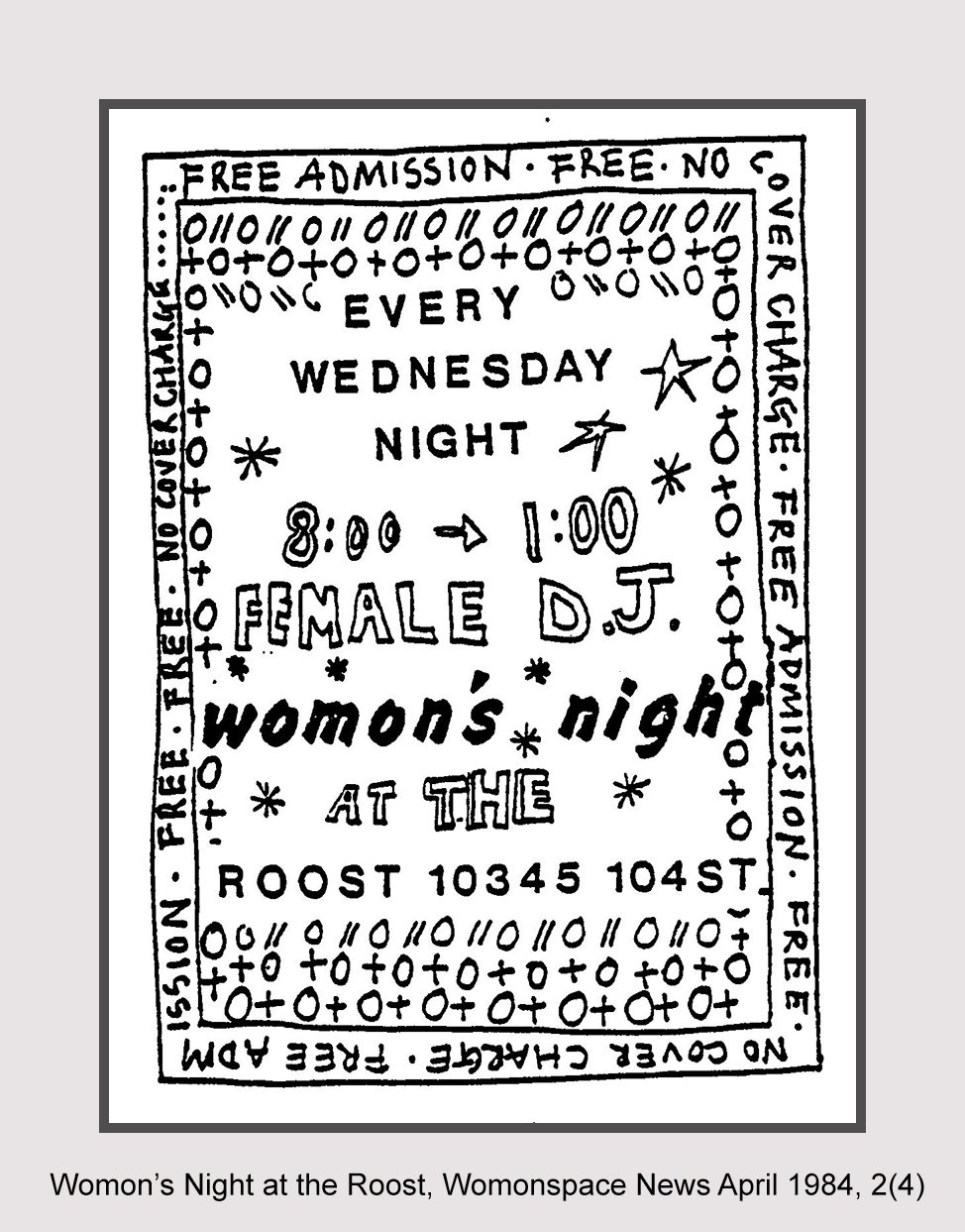

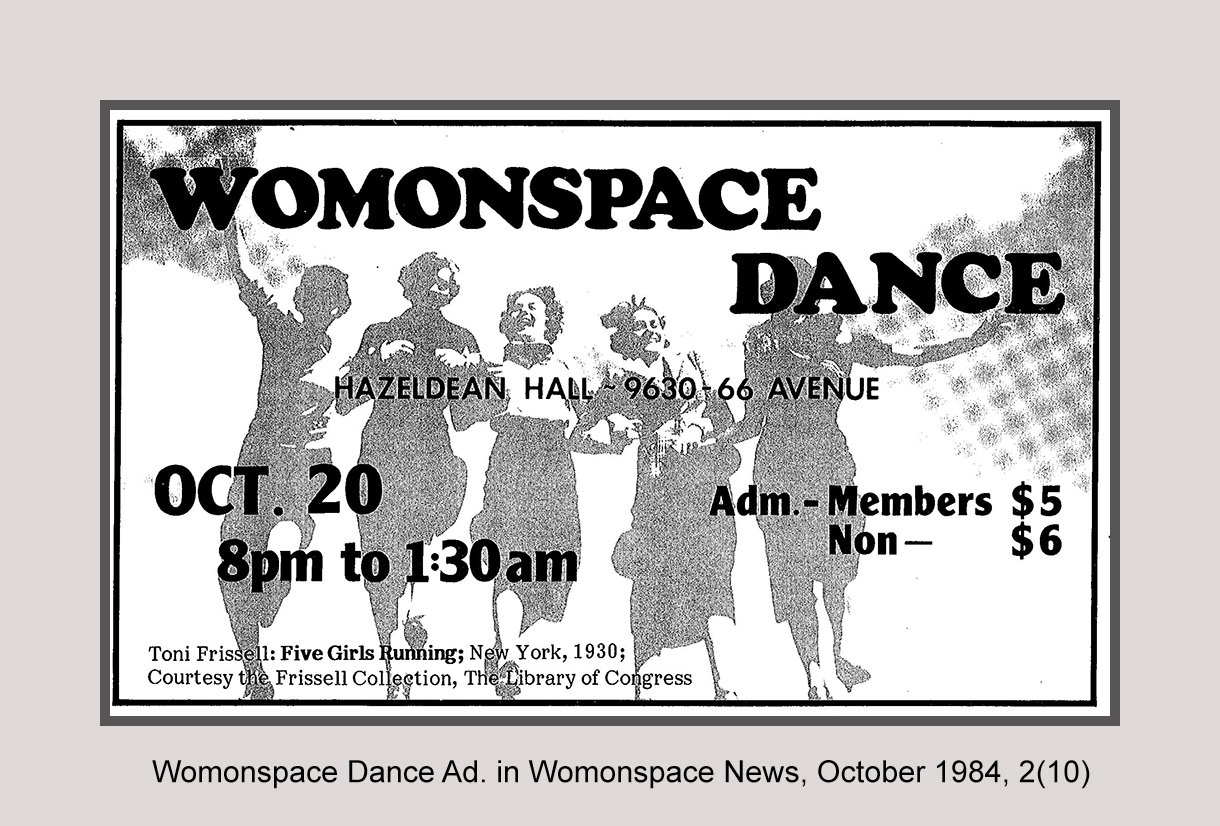

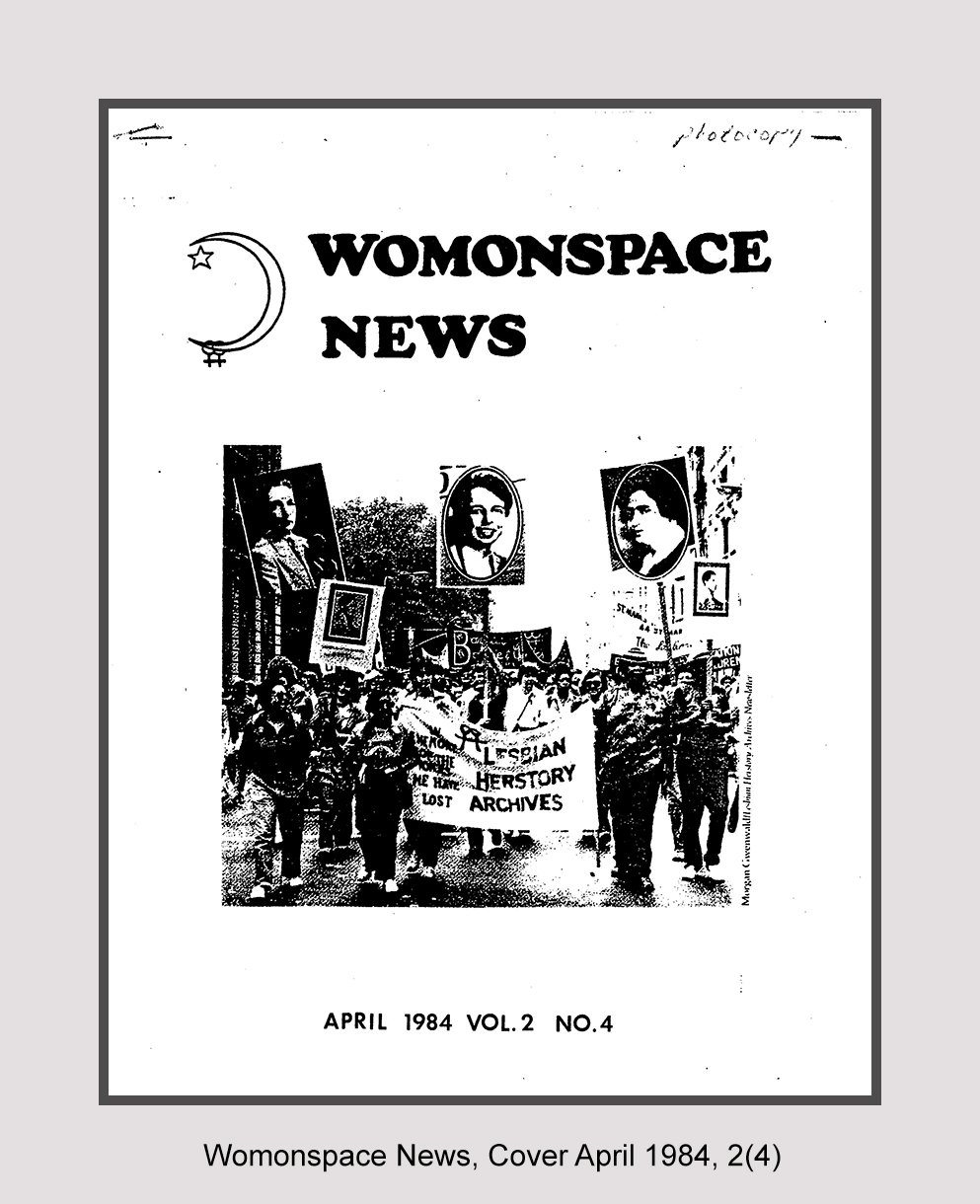

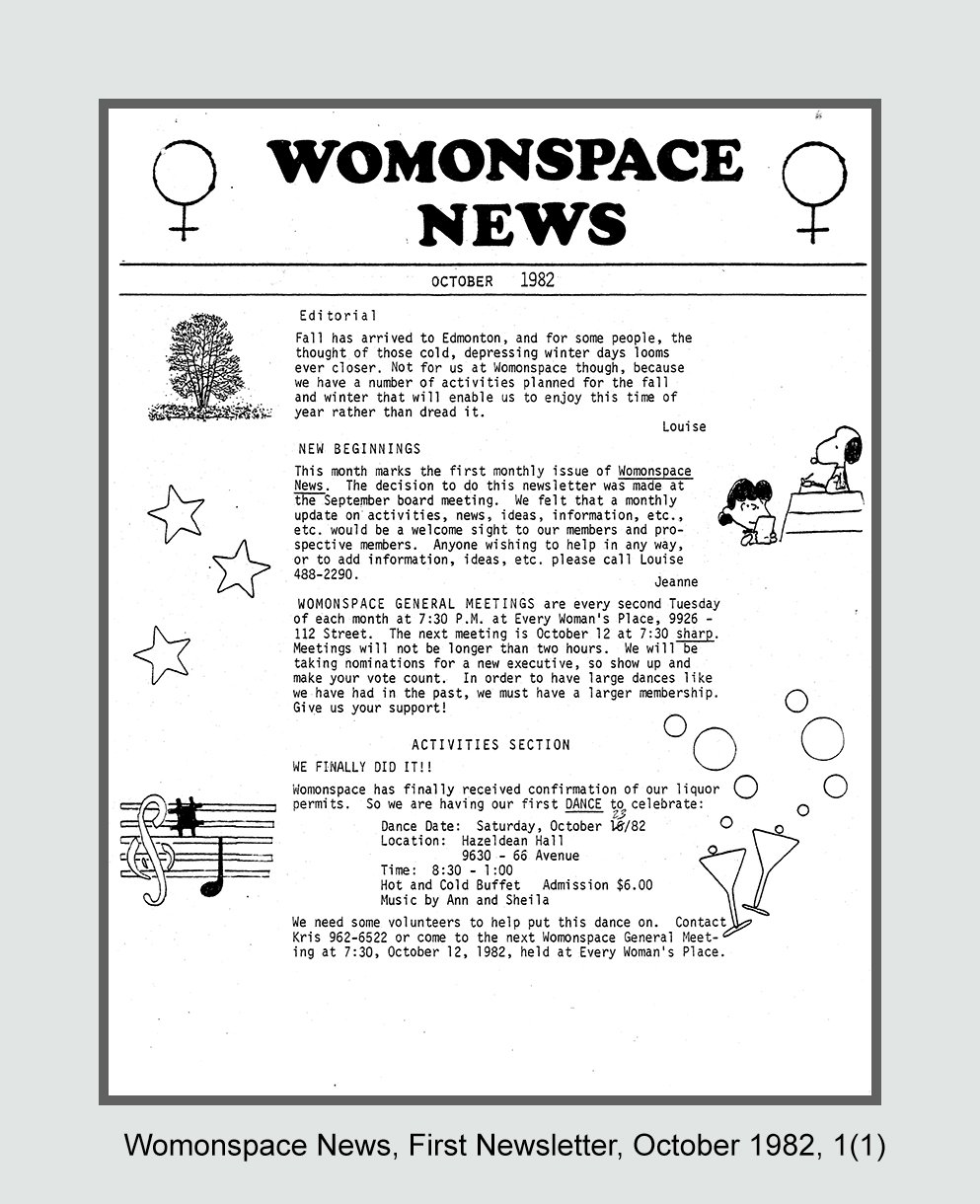

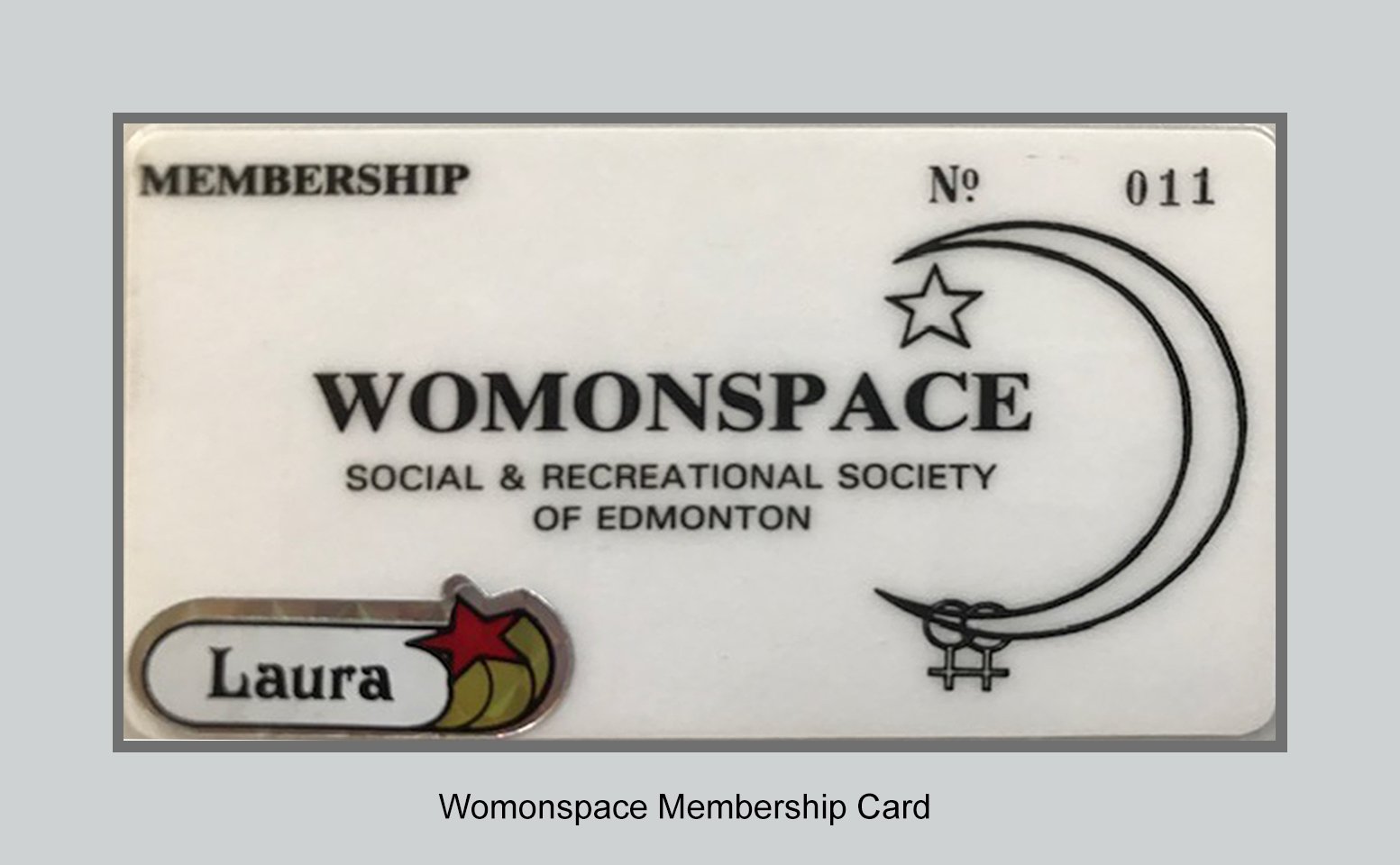

Womonspace grew organically in response to its board’s interests, needs, talents, and membership, which was composed entirely of committed volunteers . In 1982, along with being incorporated as a non-profit society, Womonspace received its first liquor license. Offering licensed dances enabled Womonspace to become financially independent of GATE and raise funds for subsequent Womonspace dances and a host of recreational, social, and educational activities. Over the years, Womonspace offered a wide variety of activities, including pool and golf tournaments, cards and games nights, gym nights, ski trips, camping trips, self-defense classes for women, softball teams, hayrides, roller skating, film nights, and safer-sex workshops.